The motivation for this article came after a long journey trying to study a bit flipping attack on the CBC (Cipher Block Chaining) mode cipher. The conclusion of my initial journey in this study took place after the construction of a CTF challenge that I created for an event by Boitatech. This article will cover the theory behind the attack.

Portuguese version: here 🇧🇷

Primitives

Before we start, we should note some interesting readings or knowledge to assist all the logic are the general concepts of cryptography, properties of XOR operations and of course, for the resolution of the examples, Python programming.

As described in Wikipedia about modes of operation including CBC, they only guarantee the confidentiality of the message, but the integrity is affected. This is very important considering the bit-flipping attack that explores precisely this property.

AES CBC

The CBC mode is one of the modes of operation of AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) a symmetric encryption algorithm, which means that the same key is used both to encrypt and decrypt the data.

Encryption

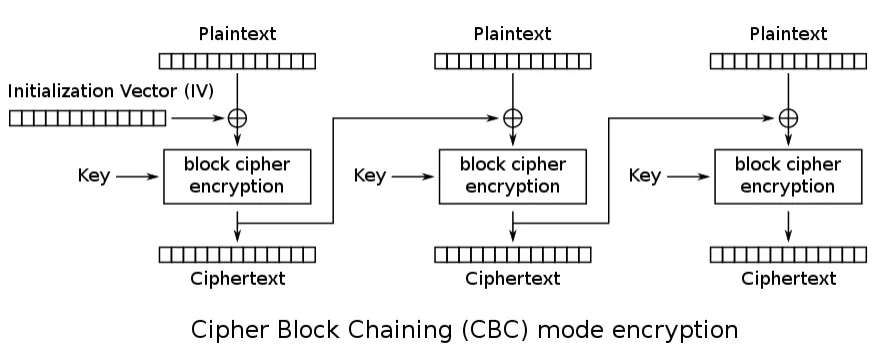

The CBC as the name says refers to the operation of the algorithm, which divides the plaintext into blocks, and each block is always considered in the operation of the following block, the following image shows the process.

As the first block does not have a previous block, what is used is the Initialization Vector, better known as IV, so an XOR operation is done being the 1st plaintext block $\oplus$ IV, the result is sent to the AES function which will result in the first block of ciphertext, note that this block also goes to the XOR of the second plaintext block and thus the process repeats itself with the other blocks.

The mathematical formula would be:

\[\large C_i=E_k(P_i \oplus C_{i-1}) \\ \large C_0=IV\]Decryption

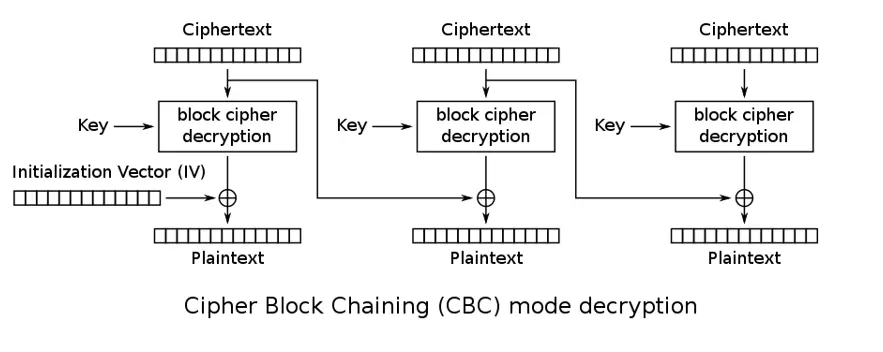

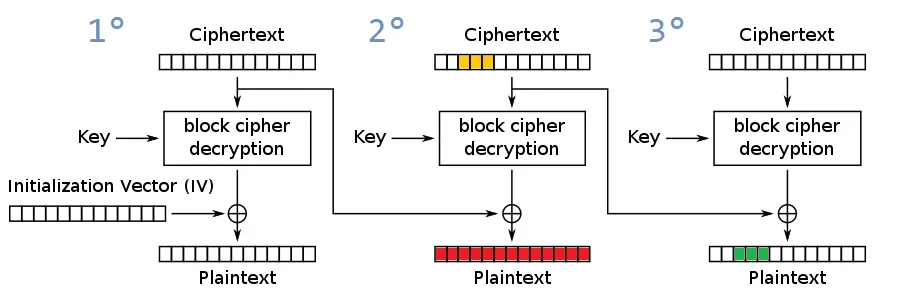

The decryption process follows the reverse logic of the encryption process. The first block of ciphertext is used in the decryption function, and this result is XORed with the IV to give the plaintext. Note that at the beginning, the first block of ciphertext is passed to the second stage in an XOR operation with the result of the decryption function of the second block. This process keeps repeating, always considering the previous blocks.

In the mathematical formula:

\[\large P_i=D_k(C_i) \oplus C_{i-1} \\ \large C_0 = IV\]The exploitation of bit-flipping, which will be addressed in the next topics, occurs due to problems in the way the CBC’s decryption process takes place. Understanding it is crucial for the execution of the attack.

Bit flipping basics

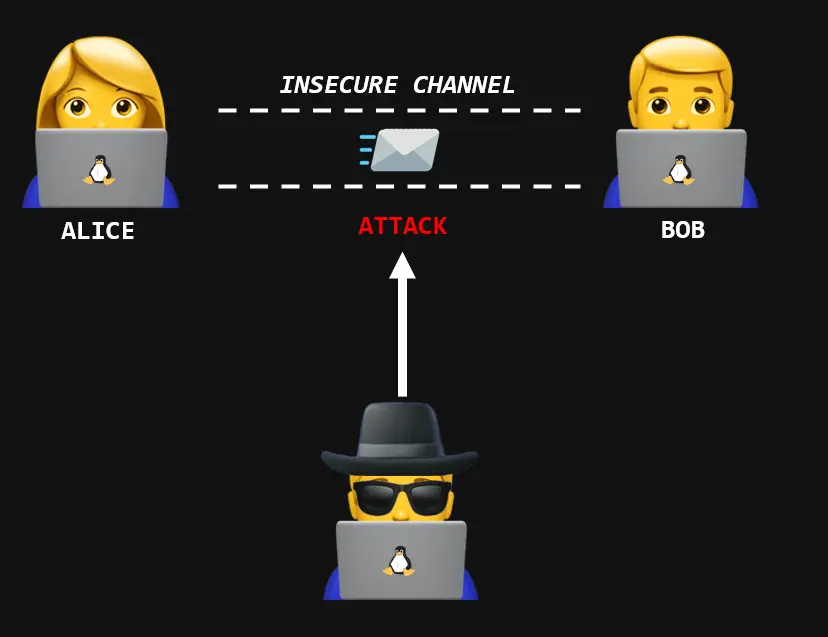

The idea of bit-flipping can be explained by considering the scenario in the image above, where there is an insecure communication channel. For the purpose of our example, let’s assume that Alice will send a message to Bob. This message will be encrypted by Alice, so what will actually be sent is the ciphertext. Eve, the attacker, will intercept the ciphertext in the channel, and by carrying out the bit-flipping attack, will modify the content of the plaintext from the ciphertext without knowing the key. Thus, when Bob decrypts the message after receiving it, he will end up with a modified plaintext. The confidentiality of the message has been maintained, as it continued to be encrypted and its plaintext confidential; however, the integrity was affected since the plaintext was altered by Eve.

TLDR; bit-flipping is altering the final plaintext

I believe things will become clearer during the exploration and examples, but keep the TLDR in mind, what we’re talking about here is modifying the content of messages without knowing the key. Throughout the article, it will become clear that there are variations of the exploitation depending on how much the attacker knows about the original plaintext and other factors related to the encryption operation in question.

Understanding the problem

As discussed earlier, the bit-flipping attack on CBC is due to the decrypt process and is related to XOR operations.

Analyzing the above image we have:

- Decrypt process being performed;

- A plaintext/ciphertext of 3 blocks of 16 bytes,

3 * 16 bytes = 48 bytes in total

For the sake of example, let’s consider the following goal: We want to change the third, fourth and fifth bytes of the third block. In this case we know the original plaintext.

To do this it will be necessary to modify the third, fourth and fifth bytes of the second block. Notice that they are part of the XOR operation: $P_3 = D_k(C_3) \oplus C_2$, being:

- $P_3$ the plaintext of the third block;

- $C_2$ the ciphertext of the second block;

- $D_k(C_3)$ the result of the decrypt of block 3;

The bit-flipping attack aims to change the final plaintext, in our case the altered plaintext will be $P_3’$, for this to happen, we should change the ciphertext, in our case the ciphertext of the previous block, we will call it $C_2’$, follows the logic:

Follow the operations below:

- Starting with:

- Considering a modified plaintext we would have:

- The common factor between the equations is $D_k(C_3)$, therefore replacing in the modified plaintext equation, we have:

Notice how the last equation turned out, we have a definition as being modified ciphertext = original plaintext $\oplus$ original previous ciphertext $\oplus$ plaintext that the attacker wants. The most interesting thing of all is that at no time do we need the key or understand the functions $E_k()$ and $D_k()$ we can reach an equation to carry out the attack just with XOR properties.

General bit flipping equation:

\[\large P_i' = P_i \oplus C_{i-1} \oplus C_{i-1}' \\ \large C_{i-1}' = P_i \oplus C_{i-1} \oplus P_i' \\ \large C_0 = IV ^ * \\ \large C_0' = IV' ^ *\]- * : It is also possible to work with the IV depending on the case, in the example of the CTF challenge covered in this article the attack involves modification of the IV

Weaponizing

Now that we have a theoretical definition about the attack and the CBC operation mode, let’s move on to practical examples. To simplify some things, we will use two python libraries:

$ pip install pycryptodome pwntools

We will start the following script to generate the ciphertext that we will attack:

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from Crypto.Util.Padding import pad, unpad

def encrypt(key, iv, plaintext):

plaintext = pad(plaintext.encode(), AES.block_size)

# add padding

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv)

ciphertext = cipher.encrypt(plaintext)

return ciphertext

# random generated 16 bytes key

key = bytes.fromhex('63f835d0e3b9c70130797be59e25c00f')

# random generated 16 bytes iv

iv = bytes.fromhex('b05fee43fe4db7c5503b1f6732fedd1b')

print('Key: ', key.hex())

print('IV: ', iv.hex())

plaintext = 'DOGECOIN transaction: 100 DOGE to [email protected]'

print('Plaintext: ', plaintext)

ciphertext = encrypt(key, iv, plaintext)

print('Ciphertext in bytes:', ciphertext)

print('Ciphertext in hex: ', ciphertext.hex())

Note that the plaintext of the example is:

plaintext = 'DOGECOIN transaction: 100 DOGE to [email protected]'

Now let’s go to the attack scenario:

Alice performs a DOGECOIN transaction and sends 100 DOGE to BOB, who has the address “[email protected]”. Eve, the attacker plans to carry out a bitflipping attack and change the destination of the bitcoins to “[email protected]”.

With the attack scenario in mind, we can then set up the modified plaintext and outline our “target” bytes.

mod_plaintext = 'DOGECOIN transaction: 100 DOGE to [email protected]'

# ^^^

In this practical example I placed the bytes to be changed in the same position as the theoretical example looking for a better understanding. Notice that the difference between the original plaintext and the modified one are only the third, fourth and fifth byte of the third block, so we have:

- B turns into E (third byte of the third block, 34° total)

- O turns into V (fourth byte of the third block, 35° total)

- B turns into E (fifth byte of the third block, 36° total)

Remembering the bit-flipping equation presented in previous topics:

\[\large C_{i-1}' = P_i \oplus C_{i-1} \oplus P_i'\]Trying to transform from mathematics to Python, we need to note that in the mathematical formula we are referring to the blocks of ciphertext/plaintext, where $i$ represents the block number, when we think in Python, a “byte by byte” operation is being performed, we are referring exactly to the position of the byte we want to modify in relation to the ciphertext/plaintext, so applying this, $i$ will now be the position of the byte to be modified in the final plaintext, now we will have to find that same position but related to the previous block, that is, going back 16 bytes, so $C_{i-1}’$ would be in python mod_ciphertext[i - 16].

target_pos = i

mod_ciphertext[i - 16] = plaintext[i] ^ ciphertext[i - 16] ^ mod_plaintext[i]

# mod_ciphertext = original_byte_plaintext ^ original_ciphertext_in_previous_block ^ malicious_mod_plaintext_byte

Notice, it’s an operation directly related to the bytes! If you are looking for an operation in python that defines this whole article, it is just above, if you have to remember something remember it!

Bit-flipping attack

To apply this operation in the script and carry out the attack, we need to modify the code a bit, adding a decrypt function (to test if the attack worked). Notice that there is a key in the code, but only to create the ciphertext and then perform the decrypt, it is not used in the attack.

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from Crypto.Util.Padding import pad, unpad

def encrypt(key, iv, plaintext):

plaintext = pad(plaintext.encode(), AES.block_size)

# add padding

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv)

ciphertext = cipher.encrypt(plaintext)

return ciphertext

def decrypt(key, iv, ciphertext):

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv)

plaintext = cipher.decrypt(ciphertext)

plaintext = unpad(plaintext, 16)

# remove padding

return plaintext

key = bytes.fromhex('63f835d0e3b9c70130797be59e25c00f')

iv = bytes.fromhex('b05fee43fe4db7c5503b1f6732fedd1b')

plaintext = 'DOGECOIN transaction: 100 DOGE to [email protected]'

original_plaintext = plaintext

ciphertext = encrypt(key, iv, plaintext)

mod_plaintext = 'DOGECOIN transaction: 100 DOGE to [email protected]'

target_pos1 = 34 # B to E

target_pos2 = 35 # O to V

target_pos3 = 36 # B to E

mod_ciphertext = bytearray(ciphertext)

# change B to E in position 34

mod_ciphertext[target_pos1 - 16] = ord('B') ^ ciphertext[target_pos1 - 16] ^ ord('E') # xor operation

# change O to V in position 35

mod_ciphertext[target_pos2 - 16] = ord('O') ^ ciphertext[target_pos2 - 16] ^ ord('V') # xor operation

# change B to E in position 36

mod_ciphertext[target_pos3 - 16] = ord('B') ^ ciphertext[target_pos3 - 16] ^ ord('E') # xor operation

print('[+] Old ciphertext: ', ciphertext.hex())

print('[+] New ciphertext: ', mod_ciphertext.hex())

print('[-] Decrypting...')

mod_plaintext = decrypt(key, iv, mod_ciphertext)

print('[+] Original plaintext: ', original_plaintext)

print('[+] Modified ciphertext ', mod_plaintext)

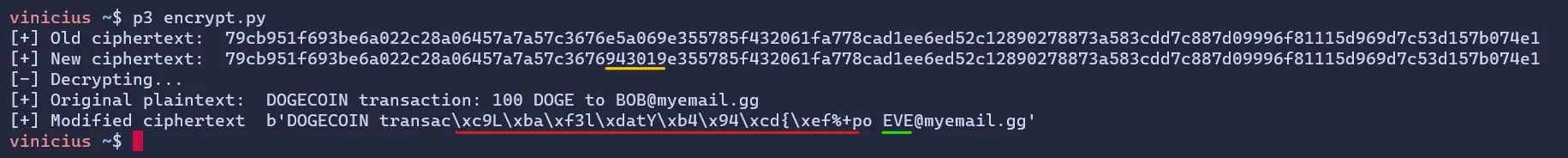

And as a result we have:

b'DOGECOIN transac\xc9L\xba\xf3l\xdatY\xb4\x94\xcd{\xef%+po [email protected]'

We managed to change the plaintext! Our malicious and modified ciphertext entered the decrypt and in the end we obtained the modified plaintext! By itself, the attack was completed, but as can be seen, the final plaintext ended up with certain strange bytes, which do not correspond to the original plaintext.

Variations

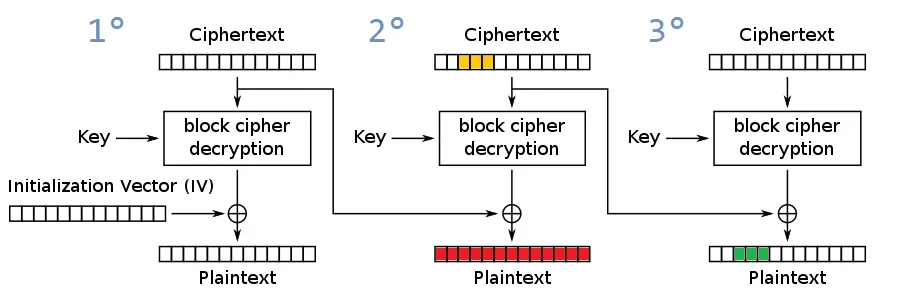

Before starting the topic of attack variations, I would like to bring back the image that represents the bit-flipping attack.

Notice the colors and identify them in the terminal print that contains the result of the attack.

- Yellow: The modified bytes of the ciphertext

- Green: The modified plaintext

- Red: The corresponding bytes of the block previous to the bytes of the modified plaintext; the entire block was affected, affecting the final plaintext.

The conclusion regarding the red part is: As the ciphertext was altered for plaintext modification, this altered block of ciphertext, when passed through the decrypt function will result in a different and altered plaintext block.

Recursively in each block

The thinking that the attacker should have at this time is a thought linked to recursion, now we have a modified ciphertext, which produces a plaintext with a malicious email address (EVE), but this plaintext has wrong bytes in the middle of it. So, with this we have the same situation as at the beginning, A plaintext that we know needs to be altered (to change the bytes that came out wrong to the correct bytes we know from the plaintext)…

In the first example, the attack was carried out byte by byte, “line by line” in python, but the ideal would be a generic function that carried out the attack. Therefore, here begins the phase of developing the algorithm to automatically perform bit-flipping attacks in CBC.

Of course, this would depend on the attacker having access to the entire result of the final plaintext, without this, it is impossible to follow the next steps. That is, in some way the attacker has to be able to send a ciphertext and obtain the result of the decrypt of this ciphertext.

Exploit

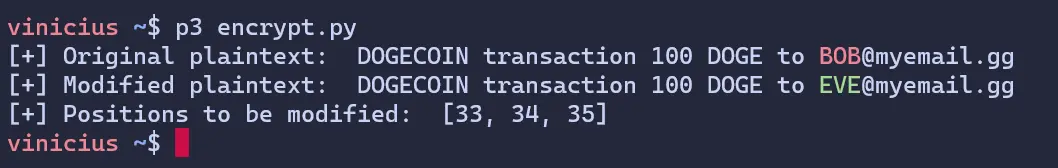

To start the automation of the attack, first it is necessary to find a way to find the differences between one set of bytes and another, in our case, between the original plaintext and the modified one, finding these differences, the positions of each byte to be modified should be saved.

Basically what we will do is a diff, and what we will use will be one of the properties of XOR:

\[\large A \oplus A = 0 \\ \large A \oplus B \ne 0\]Something XORed with itself is always Null, if it is something different from itself, it always results in something different, try to run the following script:

from termcolor import colored

from pwn import xor

def bit_flipping(original_plaintext: bytes, modified_plaintext: bytes):

diff_positions = []

for position, byte_ in enumerate(original_plaintext):

x = xor(original_plaintext[position], modified_plaintext[position]) # xor each byte

if x != b'\x00': # if the result is not null, then it is different

diff_positions.append(position)

# just to visualize what is happening in colors, ignore

og = ''

for i, b in enumerate(original_plaintext):

if i in diff_positions:

og += colored(chr(b), 'red')

else:

og += chr(b)

mod = ''

for i, byte_ in enumerate(modified_plaintext):

if i in diff_positions:

mod += colored(chr(byte_), 'green')

else:

mod += chr(byte_)

print('[+] Original plaintext: ', og)

print('[+] Modified plaintext: ', mod)

print('[+] Positions to be modified: ', diff_positions)

Output:

Now we have a way to know what must be changed and what must be kept. Following the developed logic, let’s add to the code an algorithm to change each of these plaintext bytes in these positions by changing the ciphertext in these positions - 16.

NOTE: You may have thought: “But what about the positions to be changed that are less than 16?”. For these positions we would have to change the IV, we will work with this later on, so for now we will take only the positions that are >= 16.

def bit_flipping(original_plaintext: bytes, modified_plaintext: bytes, ciphertext: bytes):

diff_positions = []

for position, byte_ in enumerate(original_plaintext):

x = xor(original_plaintext[position], modified_plaintext[position]) # xor each byte

if x != b'\x00': # if the result is not null, then it is different

diff_positions.append(position)

ciphertext = list(ciphertext)

diff_positions.reverse()

diff_positions = [position for position in diff_positions if position >= 16]

for position in diff_positions:

ciphertext[position - 16] = original_plaintext[position] ^ ciphertext[position - 16] ^ modified_plaintext[position]

ciphertext = bytes(ciphertext)

return ciphertext

original_plaintext = b'DOGECOIN transaction: 100 DOGE to [email protected]'

mod_plaintext = b'DOGECOIN transaction: 100 DOGE to [email protected]'

ciphertext = encrypt(key, iv, original_plaintext)

new_ciphertext = bit_flipping(original_plaintext, mod_plaintext, ciphertext)

print(decrypt(key, iv, new_ciphertext))

The function takes positions and changes the ciphertext of the previous block using the formula $C_{i-1}’= P_i \oplus C_{i-1} \oplus P_i’$ (line 13), and at the end returns the ciphertext.

When executed, the output is:

b'DOGECOIN transac\xc9L\xba\xf3l\xdatY\xb4\x94\xcd{\xef%+po [email protected]'

Exactly what we had before, now to play a little more, try to change more things from the last block of plaintext, using a mod_plaintext = b'DOGECOIN transaction: 100 DOGE to [email protected]' (changing the domain of the email) we get:

b'DOGECOIN transac]p\xc7P\xb6?)\xb6\xbb\x8av\x8c\xb68\x01\xe9o [email protected]'. You can see that it was changed.

Now we have a part of the exploit, a function capable of identifying the bytes to be changed and performing the attack automatically, but we still have some problems, the final plaintext is still wrong, now let’s apply the recursion that was mentioned in the previous topics.

def bit_flipping(original_plaintext: bytes, modified_plaintext: bytes, ciphertext: bytes):

diff_positions = []

for position, byte_ in enumerate(original_plaintext):

x = xor(original_plaintext[position], modified_plaintext[position]) # xor each byte

if x != b'\x00': # if the result is not null, then it is different

diff_positions.append(position)

ciphertext = list(ciphertext)

diff_positions.reverse()

diff_positions = [position for position in diff_positions if position >= 16]

for position in diff_positions:

ciphertext[position - 16] = original_plaintext[position] ^ ciphertext[position - 16] ^ modified_plaintext[position]

ciphertext = bytes(ciphertext) # this ciphertext is wrong

# recursively call the function until the modified plaintext is equal to the plaintext

mod_final_plaintext = decrypt(key, IV, ciphertext) # the attacker needs to be able to decrypt the ciphertext

new_ciphertext = ciphertext ## need to change the ciphertext again

while mod_final_plaintext[16:] != modified_plaintext[16:]:

new_ciphertext = bit_flipping(mod_final_plaintext, modified_plaintext, new_ciphertext)

mod_final_plaintext = decrypt(key, IV, new_ciphertext)

return new_ciphertext

To use recursion to our advantage, what the algorithm does is to consider the modified ciphertext that generates the strange plaintext, as a new ciphertext to be modified, so we run the function recursively (line 22) using as target the new_ciphertext (this ciphertext that generates the wrong plaintext). Note that even in the while only the 16th byte onwards is taken, this is because we have not yet started to mess with the IV.

After executing, we get:

b'\xc6\xd1\xad=\xabF\xd6\xcbE\r\x0b\xfe\xa8\x0b<Ftion: 100 DOGE to [email protected]'

It worked! Now the second block that was leaving wrong already appears, to play a little more, we can modify the transaction value to 999. Running it gives us:

b'\x08\xd4\xf1\x92\x90\x16\xd4\x07\x8c\xaa\xc4\xc9\x9c\xad\xd28tion: 999 DOGE to [email protected]'

Note that we still have a final plaintext that has wrong bytes, those belonging to the first block, how to fix it? For this we will have to enter a variation of the bitflipping attack, where the attacker can modify the IV used in the decrypt function. By changing the IV, we will be able to fix the first block, and thus we will have a 100% clean plaintext.

And how to change the IV? Using the general equation we come to:

\[\large C_{1-1}' = C_0' = IV' = P_1 \oplus IV \oplus P_1' \\ \large C_0 = IV\]In order to apply this in our algorithm, we have to modify our function by adding two new arguments, the changeiv and the iv.

def bit_flipping(original_plaintext: bytes, modified_plaintext: bytes, ciphertext: bytes, changeiv=False, iv=None):

diff_positions = []

for position, byte_ in enumerate(original_plaintext):

x = xor(original_plaintext[position], modified_plaintext[position]) # xor each byte

if x != b'\x00': # if the result is not null, then it is different

diff_positions.append(position)

ciphertext = list(ciphertext)

diff_positions.reverse()

diff_positions = [position for position in diff_positions if position >= 16]

for position in diff_positions:

ciphertext[position - 16] = original_plaintext[position] ^ ciphertext[position - 16] ^ modified_plaintext[position]

ciphertext = bytes(ciphertext) # this ciphertext is wrong

# recursively call the function until the modified plaintext is equal to the plaintext

mod_final_plaintext = decrypt(key, IV, ciphertext) # the attacker needs to be able to decrypt the ciphertext

new_ciphertext = ciphertext ## need to change the ciphertext again

while mod_final_plaintext[16:] != modified_plaintext[16:]:

new_ciphertext = bit_flipping(mod_final_plaintext, modified_plaintext, new_ciphertext)

mod_final_plaintext = decrypt(key, IV, new_ciphertext)

if changeiv == True:

# the firts 16 bytes of our modified plaintext are wrong, so we need to change the iv, lets get exactly the first 16 bytes wrongs positions of the plaintext

# like diff again

wrong_positions = []

for position, byte_ in enumerate(mod_final_plaintext[:16]):

x = xor(mod_final_plaintext[position], modified_plaintext[position])

if x != b'\x00':

wrong_positions.append(position)

# iv to change

new_iv = list(iv)

for wrong_position in wrong_positions:

new_iv[wrong_position] = mod_final_plaintext[wrong_position] ^ iv[wrong_position] ^ modified_plaintext[wrong_position]

new_iv = bytes(new_iv)

# return a tuple contaning the new ciphertext and the new iv

return new_ciphertext, new_iv

return new_ciphertext

original_plaintext = b'DOGECOIN transaction: 100 DOGE to [email protected]'

mod_plaintext = b'DOGECOIN transaction: 999 DOGE to [email protected]'

ciphertext = encrypt(key, iv, original_plaintext)

new_ciphertext, new_iv = bit_flipping(original_plaintext, mod_plaintext, ciphertext, changeiv=True, iv=iv)

print(decrypt(key, new_iv, new_ciphertext))

When checking if it is necessary to change the iv (line 26), a part of the diff is first executed, to get the exact positions of what needs to be changed, the application of the equation occurs on line 38, where the new_iv is modified using the equation. Note that there is nothing like position - 16, this is because the IV is another thing, the part of the ciphertext, what we do is just reflect the position to it, since both the first block of the ciphertext and the IV have 16 bytes of size.

After execution, the result is: b'DOGECOIN transaction: 999 DOGE to [email protected]'

Now yes, a perfect final plaintext! As usual, to play around, try to change the mod_plaintext to only empty spaces…

original_plaintext = b'DOGECOIN transaction: 100 DOGE to [email protected]'

mod_plaintext = b' '

ciphertext = encrypt(key, iv, original_plaintext)

new_ciphertext, new_iv = bit_flipping(original_plaintext, mod_plaintext, ciphertext, changeiv=True, iv=iv)

print(decrypt(key, new_iv, new_ciphertext))

Executing…

It works too, this proves that now it is possible to make any kind of change.

Conclusion

After some research, I didn’t find many attacks or vulnerabilities that specifically involve bit-flipping in CBC, I believe that so far it is a theoretical vulnerability, which is usually found in CTF cryptography challenges. I found difficulty in researching the topic due to its complexity, and because many articles are focused on specific CTF challenges, so I decided to write this article to address the topic in a general way, without CTF challenges involved, bring the theory and mathematical operations seeking to address an example and carry it to the end with the aim of building a generic algorithm/exploit for any situation (within the variations of the attack).

It is important to mention that this article was constructed from personal research and study, therefore, it may contain errors, if you find any, please let me know so I can correct it. If this happens, send an email to: [email protected] or open an issue in the repository of this blog.

Thanks for reading!